GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION

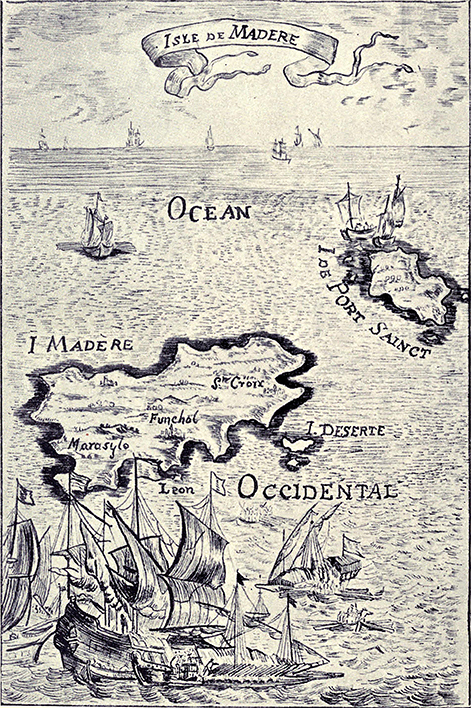

Belonging to Portugal, the island of Madeira is situated in the Atlantic Ocean, about 900Km south-west of Lisbon, and 600km west from the North African coast.

With an area of approximately 735 Km2 and a maximum length and breadth of 57Km and 23Km respectively, the island of Madeira is the largest and most important of the archipelago, which includes Madeira, Porto Santo, the Salvage and Desertas Islands.

With an area of approximately 735 Km2 and a maximum length and breadth of 57Km and 23Km respectively, the island of Madeira is the largest and most important of the archipelago, which includes Madeira, Porto Santo, the Salvage and Desertas Islands.

HISTORY

DISCOVERY OR REDISCOVERY?

There are references to the archipelago of Madeira in the manuscript “Libro del conoscimiento de todos los Reynos” and the island is marked on Italian and Catalan maps dating from the mid fourteenth century. This contradicts the theory that Madeira was only discovered by João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

Despite the documentary evidence, it is difficult to verify the exact date of discovery and the nationality of the discoverer. The island appears on the 1399 Dulcert Map, and in the 1351 Medici Atlas, as well as in other nautical documents dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The fifteenth century names of the islands of the Archipelago of Madeira are the roots of those still in use today: the Italian maps use Legname, Santo Christi and Deserte, whilst on the Spanish maps the islands are named Leiname, Puerto Santo and Disierta.

There is also a theory that the islands were visited during the reign of D. Afonso IV by one of the luso-genovian expeditions on their way to the Canaries.

The most current version of debate about the discovery or rediscovery of the Madeiran archipelago rests on the instructions given by Prince Henry the Navigator to João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira who were sent to explore the eastern coast of the African continent. Having been blown off course, they disembarked first at Porto Santo in 1419. From Porto Santo they could see another land mass densely shrouded in cloud at which they eventually arrived; this was Madeira.

The island’s importance as a navigational point was quickly recognised. Zarco and Vaz Teixeira returned to Portugal and suggested to Prince Henry that the island should be claimed as Portuguese territory and populated the following year.

The fact that the Madeiran archipelago appears in manuscripts and letters dating from the fourteenth century invalidates the belief that its discovery came about by mere chance. However, the importance of the discovery of Madeira in the history of the Portuguese Discoveries is in no way diminished by the mystery surrounding its circumstances.

Despite the documentary evidence, it is difficult to verify the exact date of discovery and the nationality of the discoverer. The island appears on the 1399 Dulcert Map, and in the 1351 Medici Atlas, as well as in other nautical documents dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The fifteenth century names of the islands of the Archipelago of Madeira are the roots of those still in use today: the Italian maps use Legname, Santo Christi and Deserte, whilst on the Spanish maps the islands are named Leiname, Puerto Santo and Disierta.

There is also a theory that the islands were visited during the reign of D. Afonso IV by one of the luso-genovian expeditions on their way to the Canaries.

The most current version of debate about the discovery or rediscovery of the Madeiran archipelago rests on the instructions given by Prince Henry the Navigator to João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira who were sent to explore the eastern coast of the African continent. Having been blown off course, they disembarked first at Porto Santo in 1419. From Porto Santo they could see another land mass densely shrouded in cloud at which they eventually arrived; this was Madeira.

The island’s importance as a navigational point was quickly recognised. Zarco and Vaz Teixeira returned to Portugal and suggested to Prince Henry that the island should be claimed as Portuguese territory and populated the following year.

The fact that the Madeiran archipelago appears in manuscripts and letters dating from the fourteenth century invalidates the belief that its discovery came about by mere chance. However, the importance of the discovery of Madeira in the history of the Portuguese Discoveries is in no way diminished by the mystery surrounding its circumstances.

CLIMATE

Throughout most of the year, Madeira is often buffed by the trade winds – tropical winds that blow from the north east in a westerly direction. The wind’s influence and the geographical positioning of the island which has its own morphological profile mean that the climatic conditions on the north and south coasts are very different one from the other.

The presence of microclimates is determined by the orographical profile of the landscape. The existence of a high central mountain range creates a sunny south coast, protected from the effects of the moisture carried by the winds, and a north coast with less exposure to the sun's rays.

The climate is temperate and typical of an island, with variations in temperature, humidity, and rainfall according to altitude. However, on the north facing side of the island there is always more rainfall and cooler temperatures.

Fog occurs frequently at different altitudes, sometimes as low as 500 m during the winter and a little higher during the summer.

The climate is therefore a temperate one, with rainfall but without regular snowfall. For most of the island, summer is not excessively hot, but it does last for a large part of the year. Along a thin strip of the south coast, the temperatures do reach high readings for most of the year.

The annual mean temperature ranges from 9ºC in the mountains and on the high plateaus, to 17.5ºC along the coast. The mean temperature for the hottest month (August) is approximately 22ºC, whilst in the coldest month (February) the reading is in the region of 15ºC.

The temperatures along the coast do not vary greatly throughout the year. The mean temperature of the hottest month is only 6ºC higher than that of the coldest month. However, in the mountain ranges, the variation is more marked, oscillating between 9 and 10ºC.

Annual relative humidity readings vary between 55% on the coast, up to approximately 90% in the areas where fog is frequent. However, at higher altitudes the readings fall back to 75%. In Funchal, the island’s capital, the mean reading is of 70%.

The levels of annual rainfall registered vary according to altitude. They range from 500mm on the south coast or 1000mm on the north coast, until approximately 3200mm in the central mountain range.

The presence of microclimates is determined by the orographical profile of the landscape. The existence of a high central mountain range creates a sunny south coast, protected from the effects of the moisture carried by the winds, and a north coast with less exposure to the sun's rays.

The climate is temperate and typical of an island, with variations in temperature, humidity, and rainfall according to altitude. However, on the north facing side of the island there is always more rainfall and cooler temperatures.

Fog occurs frequently at different altitudes, sometimes as low as 500 m during the winter and a little higher during the summer.

The climate is therefore a temperate one, with rainfall but without regular snowfall. For most of the island, summer is not excessively hot, but it does last for a large part of the year. Along a thin strip of the south coast, the temperatures do reach high readings for most of the year.

The annual mean temperature ranges from 9ºC in the mountains and on the high plateaus, to 17.5ºC along the coast. The mean temperature for the hottest month (August) is approximately 22ºC, whilst in the coldest month (February) the reading is in the region of 15ºC.

The temperatures along the coast do not vary greatly throughout the year. The mean temperature of the hottest month is only 6ºC higher than that of the coldest month. However, in the mountain ranges, the variation is more marked, oscillating between 9 and 10ºC.

Annual relative humidity readings vary between 55% on the coast, up to approximately 90% in the areas where fog is frequent. However, at higher altitudes the readings fall back to 75%. In Funchal, the island’s capital, the mean reading is of 70%.

The levels of annual rainfall registered vary according to altitude. They range from 500mm on the south coast or 1000mm on the north coast, until approximately 3200mm in the central mountain range.

GEOMORPHOLOGY AND HIDROGRAPHY

Of volcanic origin, the island of Madeira dates from the Miocene period, more specifically from the Tertiary sub-era or the Cenozoic Era.

A morphological portrait would outline a central region high above sea level, powerfully scared by erosion which has created imposing mountain massifs, deeply cut valleys and seemingly vertical basalt drops. Hidden in the mountains there are some flat plains, such as those of Paúl da Serra, Poiso and Santo de Serra. Smaller mountain platforms, known as "achadas" dot the hillsides.

The mountain range that forms Madeira’s dorsal spine creates a natural divide in the island. The north coast is approximately 8Km distant and the south coast 14Km away. About half of the island’s total surface area is 700 meters above sea level.

Approximately 65% of the island’s surface is covered by slopes of 25%; only 12% has a sloping ratio of less than 16%. Pico do Arieiro and Pico Ruivo are the highest points, measuring 1818 and 1862 meters respectively.

Some of the mountain massifs reach as far as the sea. In some areas, steep slopes, known colloquially as "lombos", "lombinhos" and "lombadas" (literally, "loins"), link the higher central region to the coast. The slopes have created deep valleys down which rainwater pours, sometimes torrentially. These water courses form the backbone of the island's irrigation.

Similar to the rest of the island, the coastline is predominately made up of high, steep sea cliffs.

The north coast is almost entirely made up of powerful cliffs measuring up to 500 / 600 meters. All along the coastline, "fajãs" or small platforms, created by rock falls as a result of erosion can be seen.

Most of the island’s arable land is made up of steep downhill slopes, with ratios of between 16% and 25%. Cultivation of crops has only been made possible by the ingenious creation of "poios" or terraces, supported by stone walls.

As was described above, most of the water channels run steeply downhill, but the levels of water vary considerably from season to season. In the winter, thanks to high levels of rainfall, the streams swell to form rivers. In the summer, the streams on the north coast still flow, whilst on the south coast they often run almost dry. The springs are particularly numerous on the north coast. These provide a more stable source of water, as they are fed by the infiltrated rainfall and underground water tables.

A morphological portrait would outline a central region high above sea level, powerfully scared by erosion which has created imposing mountain massifs, deeply cut valleys and seemingly vertical basalt drops. Hidden in the mountains there are some flat plains, such as those of Paúl da Serra, Poiso and Santo de Serra. Smaller mountain platforms, known as "achadas" dot the hillsides.

The mountain range that forms Madeira’s dorsal spine creates a natural divide in the island. The north coast is approximately 8Km distant and the south coast 14Km away. About half of the island’s total surface area is 700 meters above sea level.

Approximately 65% of the island’s surface is covered by slopes of 25%; only 12% has a sloping ratio of less than 16%. Pico do Arieiro and Pico Ruivo are the highest points, measuring 1818 and 1862 meters respectively.

Some of the mountain massifs reach as far as the sea. In some areas, steep slopes, known colloquially as "lombos", "lombinhos" and "lombadas" (literally, "loins"), link the higher central region to the coast. The slopes have created deep valleys down which rainwater pours, sometimes torrentially. These water courses form the backbone of the island's irrigation.

Similar to the rest of the island, the coastline is predominately made up of high, steep sea cliffs.

The north coast is almost entirely made up of powerful cliffs measuring up to 500 / 600 meters. All along the coastline, "fajãs" or small platforms, created by rock falls as a result of erosion can be seen.

Most of the island’s arable land is made up of steep downhill slopes, with ratios of between 16% and 25%. Cultivation of crops has only been made possible by the ingenious creation of "poios" or terraces, supported by stone walls.

As was described above, most of the water channels run steeply downhill, but the levels of water vary considerably from season to season. In the winter, thanks to high levels of rainfall, the streams swell to form rivers. In the summer, the streams on the north coast still flow, whilst on the south coast they often run almost dry. The springs are particularly numerous on the north coast. These provide a more stable source of water, as they are fed by the infiltrated rainfall and underground water tables.

SOIL

From a geological point of view, the island is predominantly made up of the results of volcanic activity (basaltic rocks, crystallite rocks, acidic trachytic rock, and others), pyroclastic material, (such as tuffs and other porous matter, the remainder of volcanic cones, runs of magna and agglomerates), and in some small areas, sedimentary rocks, usually found along the coast, in the valley and in the "fajãs".

Most of the island’s soil is made up of basaltic matter predominate varying in composition according to altitude. At low altitude this comes across in the compact, dark colours (indicating high levels of iron) of the soil and surrounding land; whilst at higher altitudes, trachytic rocks with their rough, gritty surface are more evident.

The marks left by erosion of human or natural origin stand out all over the island. The problems caused by erosion are clearly seen in the meadows, and on the island plains. These were once heavily used for grazing and are still regularly burnt. Together with heavy rainfall and strong winds, all these factors have quickly resulted in a loss of vegetation and ground cover, and therefore in the erosion of the soil.

Man has played an active role in the formation and evolution of the landscape and soil, primarily through the diverse range of agricultural practises found on the island. For example, in order to successfully work the land, the farmers have had to dominate the steep slopes by creating the stepped stone wall terraces that line the hillsides of the island.

As a result of the movement of earth necessary during the construction of these terraces, many of the secondary geological layers of the land have been disrupted. Man’s activity has also caused changes in soil density. In some cases, the landscape has been changed radically, as a result of moving excavated soil to cover previously rocky areas.

Over the years, agricultural techniques applied to the network of small terraces have further altered the structure of the soil. Particularly relevant are the movement of earth from one area to another, composting and use of silage, and irrigation practices.

All these actions will have, in their entirety, altered the natural geological profile of the island. However, the granularity of the soil and its chemical and mineral composition has not been greatly affected.

On the whole, the island’s soil is well known for its richness; and the fertility of the fields is greatly enhanced by the plentiful water supplies.

Where the soil is poor, most often due to a lack of limestone and enriching minerals such as potassium and nitrogen, farmers have had to intervene and apply corrective measures to the soil and crops. The most frequently used measures are the addition of fertilizer and lime, in order to obtain high quality crops.

Most of the island’s soil has a naturally high pH reading, denoting acidity. Therefore, lime and its derivatives are often applied as a correctional measure. As a result of this practice, much of the arable soil is close to a neutral pH, ideal for the successful growth of vines.

There are medium to low levels of organic matter found in the soils requiring regular additions of compost and manure. There are usually sufficient levels of iron and phosphorous in soil.

Most of the island’s soil is made up of basaltic matter predominate varying in composition according to altitude. At low altitude this comes across in the compact, dark colours (indicating high levels of iron) of the soil and surrounding land; whilst at higher altitudes, trachytic rocks with their rough, gritty surface are more evident.

The marks left by erosion of human or natural origin stand out all over the island. The problems caused by erosion are clearly seen in the meadows, and on the island plains. These were once heavily used for grazing and are still regularly burnt. Together with heavy rainfall and strong winds, all these factors have quickly resulted in a loss of vegetation and ground cover, and therefore in the erosion of the soil.

Man has played an active role in the formation and evolution of the landscape and soil, primarily through the diverse range of agricultural practises found on the island. For example, in order to successfully work the land, the farmers have had to dominate the steep slopes by creating the stepped stone wall terraces that line the hillsides of the island.

As a result of the movement of earth necessary during the construction of these terraces, many of the secondary geological layers of the land have been disrupted. Man’s activity has also caused changes in soil density. In some cases, the landscape has been changed radically, as a result of moving excavated soil to cover previously rocky areas.

Over the years, agricultural techniques applied to the network of small terraces have further altered the structure of the soil. Particularly relevant are the movement of earth from one area to another, composting and use of silage, and irrigation practices.

All these actions will have, in their entirety, altered the natural geological profile of the island. However, the granularity of the soil and its chemical and mineral composition has not been greatly affected.

On the whole, the island’s soil is well known for its richness; and the fertility of the fields is greatly enhanced by the plentiful water supplies.

Where the soil is poor, most often due to a lack of limestone and enriching minerals such as potassium and nitrogen, farmers have had to intervene and apply corrective measures to the soil and crops. The most frequently used measures are the addition of fertilizer and lime, in order to obtain high quality crops.

Most of the island’s soil has a naturally high pH reading, denoting acidity. Therefore, lime and its derivatives are often applied as a correctional measure. As a result of this practice, much of the arable soil is close to a neutral pH, ideal for the successful growth of vines.

There are medium to low levels of organic matter found in the soils requiring regular additions of compost and manure. There are usually sufficient levels of iron and phosphorous in soil.

VEGETATION

The island's natural vegetation has been greatly changed by human intervention, particularly by the intense and sometimes disorganised growth of villages and towns. The traditional practice of clearing the ground by setting fire to the ground cover, the use of land for grazing, and the clearing of forests, are all examples of how man has tamed the land for his use. Furthermore, many of the forests were cleared in order to provide fuel for the sugar mills, or to provide high quality timber.

Today, the island's vegetation is primarily made of forest, including indigenous species, and agricultural land. The indigenous plants of Madeira are classified as Macaronesian flora; that is native to Madeira, the Salvage Islands, the Azores, the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde Islands. Indigenous flora survives only in small areas of the island.

There are still patches of the original forest, the Laurissilva, to be found at altitudes between 600 and 1300 metres, where there are high levels of relative humidity. This forest includes Brazilian mahogany, various types of laurel trees, the Madeira mahogany and cedar trees.

Most of the area once covered by the Laurissilva is today populated by eucalyptus, acacias, and pine trees, as the conditions are ideal for their growth and propagation. However, being invasive plants, their presence causes problems in the natural balance of the land.

On the high peaks, the vegetation is thin, as only the heathers, bilberries, and Madeira Rowan succeed in resisting the cold, wind, and strong winds of the prevailing aggressive climate.

Most of the agricultural land is found at altitudes lower than 600 metres. Cultivated land is divided up into small terraces or "poios", etched into the hillside, and usually supported by stone walls.

The main crops are banana, sugar cane, grapes, and tropical fruits including avocados, custard apples, mangos, passion fruit and papaya. There are also fruit crops from more temperate climates, including chestnuts, figs, loquats, walnuts, apples, pears, oranges and lemons. Some cereals, primarily wheat and corn are grown. Other crops essential to subsistence agriculture, such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, broad beans, cabbages, beans, yams and lupins are also grown.

With the exception of bananas and sugar cane, considered to be monocultures, the remaining crops, including grapes, are generally considered to be those associated with a typical policulture agricultural system.

Today, the island's vegetation is primarily made of forest, including indigenous species, and agricultural land. The indigenous plants of Madeira are classified as Macaronesian flora; that is native to Madeira, the Salvage Islands, the Azores, the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde Islands. Indigenous flora survives only in small areas of the island.

There are still patches of the original forest, the Laurissilva, to be found at altitudes between 600 and 1300 metres, where there are high levels of relative humidity. This forest includes Brazilian mahogany, various types of laurel trees, the Madeira mahogany and cedar trees.

Most of the area once covered by the Laurissilva is today populated by eucalyptus, acacias, and pine trees, as the conditions are ideal for their growth and propagation. However, being invasive plants, their presence causes problems in the natural balance of the land.

On the high peaks, the vegetation is thin, as only the heathers, bilberries, and Madeira Rowan succeed in resisting the cold, wind, and strong winds of the prevailing aggressive climate.

Most of the agricultural land is found at altitudes lower than 600 metres. Cultivated land is divided up into small terraces or "poios", etched into the hillside, and usually supported by stone walls.

The main crops are banana, sugar cane, grapes, and tropical fruits including avocados, custard apples, mangos, passion fruit and papaya. There are also fruit crops from more temperate climates, including chestnuts, figs, loquats, walnuts, apples, pears, oranges and lemons. Some cereals, primarily wheat and corn are grown. Other crops essential to subsistence agriculture, such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, broad beans, cabbages, beans, yams and lupins are also grown.

With the exception of bananas and sugar cane, considered to be monocultures, the remaining crops, including grapes, are generally considered to be those associated with a typical policulture agricultural system.

VITICULTURE

The difficulties faced by Madeiran farmers, including those who cultivate vines, because of the orthographic characteristics of the island are notorious. Almost all the vines on the island are planted in miniscule terraces, known as "poios", criss-crossed by the red or grey of the basalt walls that support them. The traditional method of training the vines across pergolas are a classic of Madeiran viticulture, creating a magnificent and unique landscape.

Vines grow best on the sunny south facing slopes, especially those at between 350 and 750 metres of altitude.

The trellises of vines are a masterpiece of Madeiran viticulture, creating a magnificent landscape unique to the island.

The network of man-made irrigation channels, known as "levadas" extends to over 2000Km/1200 miles. This guarantees the equal distribution of water between the 1800ha/4500 acres of agricultural land, which is divided into multiple small holdings belonging to over 4000 Madeiran viticulturists.

METHODS OF TRAINING THE VINE

In the past, on the north side of the island, vines were grown along "balseiras". This method consisted of training vines along available trees (principally chestnut, oak, laurel and beech), and then either training the vine vertically or allowing them to wind through rocks or over the ground.

Although this method produced high quantities of grapes, the grapes rarely reached maturity because of limited exposure to the sun, a result of the difficulty in pruning the vine. The growers faced a number of further obstacles as a result of the vines climbing high in the trees; pruning difficulties, applying treatment for oidium, and in harvesting the grapes.

These difficulties slowly brought about a change in practice, hastened as the supporting trees were destroyed by oidium. The replacement vines were then planted in the pergola format, as seen on the south side of the island.

The pergolas on the north side of the island have to be enclosed or protected by hedges, to protect the vines from the winds and the salt spray. Fences built from heather and bracken are a familiar sight along the north coast, particularly between Seixal and Ribeira da Janela.

On the south coast, the pergola and trellis systems predominate. Although the grapes are raised above the ground, there is so little space between the vine and the earth, that weeding, pruning, tying back the vine, clearing the leaves and even harvesting is difficult.

Today, most vines in Madeira are trained along low lying trellis just above the ground, constructed in a fashion similar to that of the Vinho Verde region.

In Porto Santo, thanks to the geological and climatic conditions, most vineyards are to be found along the coast, where free standing vines are grown.

The viticultural landscape of Porto Santo constantly evolves, as new vines are planted and cordon trained.

In Madeira there is a move to convert back to the vine stock used before the period of oidium and phylloxera. Although this strategy is already being implemented by the growers, its success depends in part on the support received from the producers and exporters of Madeira wine.

Vines grow best on the sunny south facing slopes, especially those at between 350 and 750 metres of altitude.

The trellises of vines are a masterpiece of Madeiran viticulture, creating a magnificent landscape unique to the island.

The network of man-made irrigation channels, known as "levadas" extends to over 2000Km/1200 miles. This guarantees the equal distribution of water between the 1800ha/4500 acres of agricultural land, which is divided into multiple small holdings belonging to over 4000 Madeiran viticulturists.

METHODS OF TRAINING THE VINE

In the past, on the north side of the island, vines were grown along "balseiras". This method consisted of training vines along available trees (principally chestnut, oak, laurel and beech), and then either training the vine vertically or allowing them to wind through rocks or over the ground.

Although this method produced high quantities of grapes, the grapes rarely reached maturity because of limited exposure to the sun, a result of the difficulty in pruning the vine. The growers faced a number of further obstacles as a result of the vines climbing high in the trees; pruning difficulties, applying treatment for oidium, and in harvesting the grapes.

These difficulties slowly brought about a change in practice, hastened as the supporting trees were destroyed by oidium. The replacement vines were then planted in the pergola format, as seen on the south side of the island.

The pergolas on the north side of the island have to be enclosed or protected by hedges, to protect the vines from the winds and the salt spray. Fences built from heather and bracken are a familiar sight along the north coast, particularly between Seixal and Ribeira da Janela.

On the south coast, the pergola and trellis systems predominate. Although the grapes are raised above the ground, there is so little space between the vine and the earth, that weeding, pruning, tying back the vine, clearing the leaves and even harvesting is difficult.

Today, most vines in Madeira are trained along low lying trellis just above the ground, constructed in a fashion similar to that of the Vinho Verde region.

In Porto Santo, thanks to the geological and climatic conditions, most vineyards are to be found along the coast, where free standing vines are grown.

The viticultural landscape of Porto Santo constantly evolves, as new vines are planted and cordon trained.

In Madeira there is a move to convert back to the vine stock used before the period of oidium and phylloxera. Although this strategy is already being implemented by the growers, its success depends in part on the support received from the producers and exporters of Madeira wine.