CHARACTERISTICS

The geographical area corresponding to the Denomination of Origin "Madeira" covers the whole island of Madeira.

With a history of over 400 years, Madeira wine is thought to be one of the most highly esteemed and well known fortified wines in the world. Madeira wine is a fortified wine, produced under specific conditions resulting from natural and human invention, in the DOP (Denominação de Origem Protegida) of Madeira.

The traditional and original vinification process includes the halt of must fermentation using the addition of grape spirit, selection of wine for blending, and aging of the wines in wood casks, either using the natural system known as "canteiro"1 or otherwise "estufagem"2.

A defining feature of Madeira wine is the high level of alcohol present. This is a result of paralysing fermentation by adding grape spirit, which to a certain extent preserves the quantity of residual sugar in the wine. Different styles of wine, ranging from dry to sweet are producing, depending on when the spirit is added to the wine – or when the wine is fortified.

Like Port wine, Madeira stands out from table wines thanks to unique characteristics. The range of wines is very diverse, with a surprising richness and intensity of aroma, a persistence of both aroma and finish, a high level of alcohol (generally between 19 and 22% vol.), with a wide range of sweetness and very diverse colour range.

Madeira wine flaunts a range of extraordinary and attractive colour tones through the various phases of a wine’s evolution. The palate ranges from amber, to brown, to coffee with hints of a greeny–red.

The wine is mainly produced from a blend of grape varieties, predominantly the regional variety, Tinta Negra. Single varietal wines are also produced, Malvasia, Boal, Verdelho, Sercial and Terrantez all of which are white grape varieties.

1 Literally a rack used for stacking casks or pipes, but here used to designate a high quality wine that has not gone through the process of estufagem.

2 The heating process used in Madeira to advance aging.

With a history of over 400 years, Madeira wine is thought to be one of the most highly esteemed and well known fortified wines in the world. Madeira wine is a fortified wine, produced under specific conditions resulting from natural and human invention, in the DOP (Denominação de Origem Protegida) of Madeira.

The traditional and original vinification process includes the halt of must fermentation using the addition of grape spirit, selection of wine for blending, and aging of the wines in wood casks, either using the natural system known as "canteiro"1 or otherwise "estufagem"2.

A defining feature of Madeira wine is the high level of alcohol present. This is a result of paralysing fermentation by adding grape spirit, which to a certain extent preserves the quantity of residual sugar in the wine. Different styles of wine, ranging from dry to sweet are producing, depending on when the spirit is added to the wine – or when the wine is fortified.

Like Port wine, Madeira stands out from table wines thanks to unique characteristics. The range of wines is very diverse, with a surprising richness and intensity of aroma, a persistence of both aroma and finish, a high level of alcohol (generally between 19 and 22% vol.), with a wide range of sweetness and very diverse colour range.

Madeira wine flaunts a range of extraordinary and attractive colour tones through the various phases of a wine’s evolution. The palate ranges from amber, to brown, to coffee with hints of a greeny–red.

The wine is mainly produced from a blend of grape varieties, predominantly the regional variety, Tinta Negra. Single varietal wines are also produced, Malvasia, Boal, Verdelho, Sercial and Terrantez all of which are white grape varieties.

1 Literally a rack used for stacking casks or pipes, but here used to designate a high quality wine that has not gone through the process of estufagem.

2 The heating process used in Madeira to advance aging.

GRAPES

RECOMMENDED GRAPE VARIETIES

Recommended grape varieties:

White: Folgasão (Terrantez*), Malvasia-Cândida, Malvasia-de-São-Jorge (Malvasia, Malvazia), Malvasia-Fina (Boal, Bual), Moscatel Graúdo (Moscatel-de-Setúbal), Sercial (Esgana-Cão), Verdelho.

Red/Rosé: Bastardo (graciosa), Tinta, Tinta Negra (Molar, Saborinho), Verdelho Tinto, Malvasia-Cândida-Roxa and Listrão.

Authorised grape varieties:

White: Caracol, Rio-Grande and Valveirinho.

Red: Complexa, Deliciosa and Triunfo.

The revised terminology for the different grape varieties and their recognised synonyms has been published by Portaria nº 380 from 22nd November 2012.

* Boal, Bual and Terrantez are the only synonyms authorised for labelling DOP Madeira, and refer to Malvasia Fina and Folgasão respectively.

The principal white grape varieties used in the production of Madeira wine are Sercial, Verdelho, Boal and Malvasia, whilst Tinta Negra is the main red grape.

Tinta Negra is also the most widely planted grape variety. After the phylloxera plague at the end of the nineteenth century (1872) it became the principal vinifera (European) grape variety on the island.

Other varieties, principally Bastardo, Moscatel, Listrão and Terrantez, are held in high esteem thanks to the excellent, and now increasingly rare, wine they produced. A local ditty has been coined about Terrantez:

Recommended grape varieties:

White: Folgasão (Terrantez*), Malvasia-Cândida, Malvasia-de-São-Jorge (Malvasia, Malvazia), Malvasia-Fina (Boal, Bual), Moscatel Graúdo (Moscatel-de-Setúbal), Sercial (Esgana-Cão), Verdelho.

Red/Rosé: Bastardo (graciosa), Tinta, Tinta Negra (Molar, Saborinho), Verdelho Tinto, Malvasia-Cândida-Roxa and Listrão.

Authorised grape varieties:

White: Caracol, Rio-Grande and Valveirinho.

Red: Complexa, Deliciosa and Triunfo.

The revised terminology for the different grape varieties and their recognised synonyms has been published by Portaria nº 380 from 22nd November 2012.

* Boal, Bual and Terrantez are the only synonyms authorised for labelling DOP Madeira, and refer to Malvasia Fina and Folgasão respectively.

The principal white grape varieties used in the production of Madeira wine are Sercial, Verdelho, Boal and Malvasia, whilst Tinta Negra is the main red grape.

Tinta Negra is also the most widely planted grape variety. After the phylloxera plague at the end of the nineteenth century (1872) it became the principal vinifera (European) grape variety on the island.

Other varieties, principally Bastardo, Moscatel, Listrão and Terrantez, are held in high esteem thanks to the excellent, and now increasingly rare, wine they produced. A local ditty has been coined about Terrantez:

As uvas Terrantez

Não as comas nem as dês

Para vinho Deus as fez.

Não as comas nem as dês

Para vinho Deus as fez.

"Terrantez grapes either eat or give them away, for God meant them for wine"

SERCIAL

Sercial and Verdelho together are the traditional grape varieties representing less than 2% of grapes currently produced. The move toward traditional grape varieties will certainly contribute to an increase in its production.

Different variants of Sercial are planted in many wine regions on mainland Portugal, where it is often known as "Esgana Cão" (literally "dog strangler"), due to its marked astringency and high acidity.

"Sercial", a white grape variety, was planted in great quantity in Madeira before phylloxera arrives to Madeira Island.

It was traditionally cultivated in Funchal, Câmara de Lobos, Fajã dos Padres, Campanário, Paúl do Mar and Fajã (Ponta do Pargo).

Today, it is mostly found on the north side of the island in Seixal, Porto Moniz, Ponta Delgada, São Vicente and Arco de São Jorge. On the south of the island, it is planted mainly in Jardim da Serra and at an altitude of between 600 and 700 metres.

For many years, it was thought that Sercial was related to Riesling, the German grape variety which produces what is considered to be one of the finest white wines of the world. Like Riesling, Sercial has the ability to produce wines of great longevity, and is capable of producing a wine in a house style without losing any of the inherent characteristics of the grape. However, there is no proof of any link between the two varieties.

WINES

Sercial produces light bodied wines, dry and acidic. Young wines appear stringent and unpleasant, but when they can be aged for a long period, the wine is transformed into one of the finest and most delicate of Madeira’s.

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous growth, with a medium, irregular production, averagely resistant to oidium, mildew and dry rot.

Shoots: thick and short, clear light grey colour; short internodes, very variable in spacing, thick and sometimes twisted.

Leaves: medium or large, downy on the underside, small follicles on the topside, with visible 3 lobules on the upper side, whilst only lightly traced on the underside; the top lobe is always larger and more pointed than the lateral ones; shallow unequal serrations; open upper lateral sinuses and footstalk.

Tendrils: intermittent, long and forked.

Bunches: medium size bunches on average no bigger than 20cm, compact, light, conical, found on the fourth or fifth knot; medium and woody bunchstem.

Grapes: medium, elliptical – oblong grapes, golden green, not very waxy, remainder of the flower visible, and well attached to the pedicle; a greeny pulp, meaty and succulent; medium, whitened straight brush; thick short pedicles, acidic flavour.

Produce must with high levels of acidity, and with the potential for alcoholic levels of not more than 11º.

Sercial and Verdelho together are the traditional grape varieties representing less than 2% of grapes currently produced. The move toward traditional grape varieties will certainly contribute to an increase in its production.

Different variants of Sercial are planted in many wine regions on mainland Portugal, where it is often known as "Esgana Cão" (literally "dog strangler"), due to its marked astringency and high acidity.

"Sercial", a white grape variety, was planted in great quantity in Madeira before phylloxera arrives to Madeira Island.

It was traditionally cultivated in Funchal, Câmara de Lobos, Fajã dos Padres, Campanário, Paúl do Mar and Fajã (Ponta do Pargo).

Today, it is mostly found on the north side of the island in Seixal, Porto Moniz, Ponta Delgada, São Vicente and Arco de São Jorge. On the south of the island, it is planted mainly in Jardim da Serra and at an altitude of between 600 and 700 metres.

For many years, it was thought that Sercial was related to Riesling, the German grape variety which produces what is considered to be one of the finest white wines of the world. Like Riesling, Sercial has the ability to produce wines of great longevity, and is capable of producing a wine in a house style without losing any of the inherent characteristics of the grape. However, there is no proof of any link between the two varieties.

WINES

Sercial produces light bodied wines, dry and acidic. Young wines appear stringent and unpleasant, but when they can be aged for a long period, the wine is transformed into one of the finest and most delicate of Madeira’s.

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous growth, with a medium, irregular production, averagely resistant to oidium, mildew and dry rot.

Shoots: thick and short, clear light grey colour; short internodes, very variable in spacing, thick and sometimes twisted.

Leaves: medium or large, downy on the underside, small follicles on the topside, with visible 3 lobules on the upper side, whilst only lightly traced on the underside; the top lobe is always larger and more pointed than the lateral ones; shallow unequal serrations; open upper lateral sinuses and footstalk.

Tendrils: intermittent, long and forked.

Bunches: medium size bunches on average no bigger than 20cm, compact, light, conical, found on the fourth or fifth knot; medium and woody bunchstem.

Grapes: medium, elliptical – oblong grapes, golden green, not very waxy, remainder of the flower visible, and well attached to the pedicle; a greeny pulp, meaty and succulent; medium, whitened straight brush; thick short pedicles, acidic flavour.

Produce must with high levels of acidity, and with the potential for alcoholic levels of not more than 11º.

VERDELHO

This was the most widely grown wide grape variety cultivated in Madeira, before phylloxera stuck. It is thought that it would have represented 2/3 of all the grape vines planted. There was also a red variety once planted, known as a Verdelho Tinto.

Verdelho also grows in the Azores (Ilha do Pico, Terceira and Graciosa) and Australia where it was taken from the island of Madeira around 1824.

Several authors believe, mistakenly, that is equal to Gouveio grown in the Portuguese mainland. It is different from Verdecchio from Italy and Verdejo form Spain.

Verdelho and Sercial are the least produced traditional grape varieties, currently representing 2% of total grape production. The move towards traditional grape stocks and Verdelho’s potential for producing excellent dry white table wine, will certainly promote greater production of this variety.

It is grown on the north side of the island, mainly in São Vicente, Seixal, Arco de São Jorge, Ponta Delgada and Ribeira da Janela. It is found in smaller quantities in the south, principally in Prazeres, Fajã da Ovelha and Estreito de Câmara de Lobos.

WINES

Verdelho produces wines that are slightly more full bodied but less acidic than those made from the Sercial grape. On the whole they are medium – dry wines, good on the nose, with strong hints of dry fruit. With age they develop an extraordinary smoky complexity, whilst still retaining their penetrating character.

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous, with a regular low to medium production, sensitive to Oidium (Oidium Tuckeri)

Shoots: elliptical – rounded, sometimes angular, grooved, dark brown with darker or grey patches. Short internodes, variable, thick and sometimes twisted.

Leaves: medium, rounded, wavy, slightly hairy on the topside, downy on the lower side, but in irregular patches so that it is nearly bare in some parts, shallow lobes or even just traced in, with obtuse and pointed serrations, footstalk usually tightly closed.

Tendrils: intermittent, long, forked or sometime trifurcated.

Bunches: medium or small bunches, compact, simple or light, cylindrical or conical, found between the 3rd or 4th node, short woody bunch stem.

Grapes: on average between 15/20mm, elliptical or elliptical-oblong, dark brown, with a slight waxy bloom, remainder of flower visible, lightly attached to the pedicle; a yellow-chestnut pulp, meaty and succulent; long straight and white brush ; short pedicles, short and thin pedicles; sweet flavour and lightly acidic.

Produces must with marked acidity and with a potential alcohol of between 10 and 12º.

This was the most widely grown wide grape variety cultivated in Madeira, before phylloxera stuck. It is thought that it would have represented 2/3 of all the grape vines planted. There was also a red variety once planted, known as a Verdelho Tinto.

Verdelho also grows in the Azores (Ilha do Pico, Terceira and Graciosa) and Australia where it was taken from the island of Madeira around 1824.

Several authors believe, mistakenly, that is equal to Gouveio grown in the Portuguese mainland. It is different from Verdecchio from Italy and Verdejo form Spain.

Verdelho and Sercial are the least produced traditional grape varieties, currently representing 2% of total grape production. The move towards traditional grape stocks and Verdelho’s potential for producing excellent dry white table wine, will certainly promote greater production of this variety.

It is grown on the north side of the island, mainly in São Vicente, Seixal, Arco de São Jorge, Ponta Delgada and Ribeira da Janela. It is found in smaller quantities in the south, principally in Prazeres, Fajã da Ovelha and Estreito de Câmara de Lobos.

WINES

Verdelho produces wines that are slightly more full bodied but less acidic than those made from the Sercial grape. On the whole they are medium – dry wines, good on the nose, with strong hints of dry fruit. With age they develop an extraordinary smoky complexity, whilst still retaining their penetrating character.

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous, with a regular low to medium production, sensitive to Oidium (Oidium Tuckeri)

Shoots: elliptical – rounded, sometimes angular, grooved, dark brown with darker or grey patches. Short internodes, variable, thick and sometimes twisted.

Leaves: medium, rounded, wavy, slightly hairy on the topside, downy on the lower side, but in irregular patches so that it is nearly bare in some parts, shallow lobes or even just traced in, with obtuse and pointed serrations, footstalk usually tightly closed.

Tendrils: intermittent, long, forked or sometime trifurcated.

Bunches: medium or small bunches, compact, simple or light, cylindrical or conical, found between the 3rd or 4th node, short woody bunch stem.

Grapes: on average between 15/20mm, elliptical or elliptical-oblong, dark brown, with a slight waxy bloom, remainder of flower visible, lightly attached to the pedicle; a yellow-chestnut pulp, meaty and succulent; long straight and white brush ; short pedicles, short and thin pedicles; sweet flavour and lightly acidic.

Produces must with marked acidity and with a potential alcohol of between 10 and 12º.

BOAL

Although this is a very popular variety throughout Portugal, it has become best known in Madeira, where it became anglicised into "Bual". Together with Malvasia, it is the most widely planted white grape variety, representing approximately 5% of all grape production.

It has spread throughout Campanário, Câmara de lobos, Santo António, Estreito de Câmara de Lobos, Paúl do Mar and Fajã (Ponta do Pargo). Today it is grown mainly in warm locations on the south of the island, namely Calheta, Estreito da Calheta, Arco da Calheta, Câmara de Lobos, Estreito de Câmara de Lobos and Campanário. Although it is cultivated on the north side of the island, the quantity produced from these vineyards is insignificant in relation to the total volume produced on the island.

WINES

It produces rich wines, medium-sweet and dark, medium bodied and fruity, with excellent potential to age well. It can be enjoyed whilst still young; younger than a Verdelho or a Sercial.

As it ages in cask, it becomes an attractive, well rounded wine, retaining some acidity.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous, producing medium quantities: sensitive to oidium and to mildew.

Shoots: light greyish colouring, with short internodes.

Leaves: medium, downy on the underside, small follicle on the topside, with the three lobes of the upper being clearly visible, sometimes pointed, whilst those on the underside are usually not prominent; uneven serration, usually obtuse and less pointy, a slightly open footstalk; upper lateral sinuses are often hardly visible, thanks to the prominence of the lobe.

Tendrils: intermittent.

Bunches: large or medium sized, light, dense, short bunch stem, with slight woodiness.

Grapes: average and uniform. Elliptically shaped, between 15/22mm, hard; a yellowy-green skin, golden when ripe, very sweet. A soft and succulent pulp, slightly bland. Short and sticky pedicles. Produces musts with a potential alcohol of between 11 and 13º.

Although this is a very popular variety throughout Portugal, it has become best known in Madeira, where it became anglicised into "Bual". Together with Malvasia, it is the most widely planted white grape variety, representing approximately 5% of all grape production.

It has spread throughout Campanário, Câmara de lobos, Santo António, Estreito de Câmara de Lobos, Paúl do Mar and Fajã (Ponta do Pargo). Today it is grown mainly in warm locations on the south of the island, namely Calheta, Estreito da Calheta, Arco da Calheta, Câmara de Lobos, Estreito de Câmara de Lobos and Campanário. Although it is cultivated on the north side of the island, the quantity produced from these vineyards is insignificant in relation to the total volume produced on the island.

WINES

It produces rich wines, medium-sweet and dark, medium bodied and fruity, with excellent potential to age well. It can be enjoyed whilst still young; younger than a Verdelho or a Sercial.

As it ages in cask, it becomes an attractive, well rounded wine, retaining some acidity.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous, producing medium quantities: sensitive to oidium and to mildew.

Shoots: light greyish colouring, with short internodes.

Leaves: medium, downy on the underside, small follicle on the topside, with the three lobes of the upper being clearly visible, sometimes pointed, whilst those on the underside are usually not prominent; uneven serration, usually obtuse and less pointy, a slightly open footstalk; upper lateral sinuses are often hardly visible, thanks to the prominence of the lobe.

Tendrils: intermittent.

Bunches: large or medium sized, light, dense, short bunch stem, with slight woodiness.

Grapes: average and uniform. Elliptically shaped, between 15/22mm, hard; a yellowy-green skin, golden when ripe, very sweet. A soft and succulent pulp, slightly bland. Short and sticky pedicles. Produces musts with a potential alcohol of between 11 and 13º.

MALVASIA

Despite the part that Sercial, Verdelho, Boal, Bastardo, Terrantez and Tinta da Madeira have played in the history of Madeira wine, Malvasia is without a doubt the variety that has made the wine famous since the days of the first settlers. There are a number of varieties of Malvasia planted on the island, including Cândida, Roxa, Babosa and Malvasia itself.

Tradition has it that Malvasia was the first variety to be introduced to the island by order of Prince Henry the Navigator, who in 1445 ordered the first shoots to be brought from the Mediterranean.

In Madeira, Malvasia has flourished in coastal areas along the southern side of the island, stretching through Fajã dos Padres (Campanário), Paúl do Mar, Jardim do Mar, Arco da Calheta, Madalena do Mar, Sítio do Lugar (Ribeira Brava) and Anjos (Canhas).

Today, it is mostly found growing at altitudes of between 200 and 300 metres on the north side of the island in São Jorge, Arco de São Jorge and Santana, (all towns in the district of Santana). However, the best Malvasia grows on the south of the island, specifically in Câmara de Lobos, Estreito da Calheta and Campanário. The near mythological Malvasia grapes grown in Fajã dos Padres, now produce no more than token quantity of wine.

Malvasia represents approximately 5% of the total volume of grapes produced on the island, and is, together with Boal, the most widely planted white grape variety. The most commonly planted Malvasia variety is that of Malvasia de São Jorge, but fortunately the movement to reconvert vine stock has encouraged the resurgence of Malvasia Cândida, which thrives when planted in sites at low altitude.

WINES

Malvasia produces the darkest, richest, most characterful, full bodied and fruity of all Madeira wines. It gives a smooth texture and a full body to the best wines, urbane and reminiscent of sultanas, but retains a streak of acidity which stops the wines from becoming cloying. Wines made from this variety are often known as Malmsey, from the anglicised version of Malvasia.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous and only considered to be abundantly fertile in the first years after plantation. Prone to oidium and mildew.

It is particularly sensitive to location, and climatic conditions.

It thrives at low altitudes (approximately 100 to 200 metres above sea level) in sites where good exposure to the heat of the sun protects it from the humidity and mildew to which it is extremely sensitive.

Shoots: with greyish – yellowish tones or nut brown with short or average internodes.

Leaves: rounded, of medium size, nearly smooth on both sides, with 5 deep lobes, usually sharply pointed; uneven serrations, triangular, pointed; lateral sinuses almost always tracing an open U shape, with an open footstalk, also shaped as a U.

Tendrils: intermittent.

Bunches: medium to large bunches, conically shaped, compact or slack, almost always very light; medium bunchstem, slightly woody.

Grapes: of medium size, rounded, generally between 17/20 mm; soft or slightly firm; with a yellowy – green colour, golden when ripe; susceptible to pruinose (a fine powder or waxy bloom). Large and woody pedicles (stalks) a clear pulp, soft in consistency, not very succulent and with a distinctive taste. Produces must with potential alcohol of no more than 13º.

Despite the part that Sercial, Verdelho, Boal, Bastardo, Terrantez and Tinta da Madeira have played in the history of Madeira wine, Malvasia is without a doubt the variety that has made the wine famous since the days of the first settlers. There are a number of varieties of Malvasia planted on the island, including Cândida, Roxa, Babosa and Malvasia itself.

Tradition has it that Malvasia was the first variety to be introduced to the island by order of Prince Henry the Navigator, who in 1445 ordered the first shoots to be brought from the Mediterranean.

In Madeira, Malvasia has flourished in coastal areas along the southern side of the island, stretching through Fajã dos Padres (Campanário), Paúl do Mar, Jardim do Mar, Arco da Calheta, Madalena do Mar, Sítio do Lugar (Ribeira Brava) and Anjos (Canhas).

Today, it is mostly found growing at altitudes of between 200 and 300 metres on the north side of the island in São Jorge, Arco de São Jorge and Santana, (all towns in the district of Santana). However, the best Malvasia grows on the south of the island, specifically in Câmara de Lobos, Estreito da Calheta and Campanário. The near mythological Malvasia grapes grown in Fajã dos Padres, now produce no more than token quantity of wine.

Malvasia represents approximately 5% of the total volume of grapes produced on the island, and is, together with Boal, the most widely planted white grape variety. The most commonly planted Malvasia variety is that of Malvasia de São Jorge, but fortunately the movement to reconvert vine stock has encouraged the resurgence of Malvasia Cândida, which thrives when planted in sites at low altitude.

WINES

Malvasia produces the darkest, richest, most characterful, full bodied and fruity of all Madeira wines. It gives a smooth texture and a full body to the best wines, urbane and reminiscent of sultanas, but retains a streak of acidity which stops the wines from becoming cloying. Wines made from this variety are often known as Malmsey, from the anglicised version of Malvasia.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous and only considered to be abundantly fertile in the first years after plantation. Prone to oidium and mildew.

It is particularly sensitive to location, and climatic conditions.

It thrives at low altitudes (approximately 100 to 200 metres above sea level) in sites where good exposure to the heat of the sun protects it from the humidity and mildew to which it is extremely sensitive.

Shoots: with greyish – yellowish tones or nut brown with short or average internodes.

Leaves: rounded, of medium size, nearly smooth on both sides, with 5 deep lobes, usually sharply pointed; uneven serrations, triangular, pointed; lateral sinuses almost always tracing an open U shape, with an open footstalk, also shaped as a U.

Tendrils: intermittent.

Bunches: medium to large bunches, conically shaped, compact or slack, almost always very light; medium bunchstem, slightly woody.

Grapes: of medium size, rounded, generally between 17/20 mm; soft or slightly firm; with a yellowy – green colour, golden when ripe; susceptible to pruinose (a fine powder or waxy bloom). Large and woody pedicles (stalks) a clear pulp, soft in consistency, not very succulent and with a distinctive taste. Produces must with potential alcohol of no more than 13º.

TINTA NEGRA

Tinta Negra is the most widely planted variety on Madeira, cultivated mainly in Estreito de Câmara de Lobos and Câmara de Lobos on the south of the island, and in São Vicente on the north. It currently represents 85% of the total production of the island’s grapes.

Although its history is unknown, it is sometimes thought to be the result of a cross between Pinot Noir, the great burgundy red grape variety, with Grenache.

For many years, this variety was unjustly denigrated, in favour of the other varieties that made Madeira wine famous.

Tinta Negra is a versatile variety, resistant to disease, and produces well. Traditionally, it is thought if local methods are followed during production, that wines made from this variety will take on the characteristics of other varieties according to the altitude that that the grapes came from.

This belief meant that a number of wines made using Tinta Negra, were in fact labelled with the names of the noble grape varieties. This was particularly prevalent in the periods following the decimation by oidium and phylloxera of the island’s vineyards. In fact, after phylloxera had devastated the island’s vine stocks, particularly those of Sercial, Verdelho, Boal and Malvasia, Tinta Negra, rather than the original variety was commonly used to define a style of Madeira.

Opinion about the capabilities of Tinta Negra has since changed. When the ripening period is monitored, and providing careful vinification is carried out, overseen by a skilful oenologist, Negra Mole is capable of producing interesting, and high quality, wines.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous and very productive; of medium thickness; adherent bark, dark brown; and infrequently attacked by cryptogenic diseases.

Shoots: short and thick; a red-grey, light brown or chestnut red colour; short internodes.

Leaves: medium. Unequal and irregular in shape, sometime a little concave, slightly downy on the upperside, and some with visible lobes, the upper ones deep and pointed, or obtuse, others with only lightly traced lobes; triangular or closed serrations; usually with a red tinge when adult; heartshaped footstalk.

Tinta Negra is easily identified by its leaves, which in autumn are an intense scarlet colour, with red patches.

Tendrils: few.

Bunches: medium to large bunches; globular or elliptical – globular grapes, equal or unequal, of 12/18mm, soft or not very hard, red with a clear colour

Grapes: medium and uniformly round, generally between 12/25mm; not very hard, a red colour when ripe; and not very waxy. A clear pulp, medium consistency, very succulent. The musts are not particularly concentrated, with a potential alcohol of between 9 and 12ºC.

Tinta Negra is the most widely planted variety on Madeira, cultivated mainly in Estreito de Câmara de Lobos and Câmara de Lobos on the south of the island, and in São Vicente on the north. It currently represents 85% of the total production of the island’s grapes.

Although its history is unknown, it is sometimes thought to be the result of a cross between Pinot Noir, the great burgundy red grape variety, with Grenache.

For many years, this variety was unjustly denigrated, in favour of the other varieties that made Madeira wine famous.

Tinta Negra is a versatile variety, resistant to disease, and produces well. Traditionally, it is thought if local methods are followed during production, that wines made from this variety will take on the characteristics of other varieties according to the altitude that that the grapes came from.

This belief meant that a number of wines made using Tinta Negra, were in fact labelled with the names of the noble grape varieties. This was particularly prevalent in the periods following the decimation by oidium and phylloxera of the island’s vineyards. In fact, after phylloxera had devastated the island’s vine stocks, particularly those of Sercial, Verdelho, Boal and Malvasia, Tinta Negra, rather than the original variety was commonly used to define a style of Madeira.

Opinion about the capabilities of Tinta Negra has since changed. When the ripening period is monitored, and providing careful vinification is carried out, overseen by a skilful oenologist, Negra Mole is capable of producing interesting, and high quality, wines.

MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION

Vine: vigorous and very productive; of medium thickness; adherent bark, dark brown; and infrequently attacked by cryptogenic diseases.

Shoots: short and thick; a red-grey, light brown or chestnut red colour; short internodes.

Leaves: medium. Unequal and irregular in shape, sometime a little concave, slightly downy on the upperside, and some with visible lobes, the upper ones deep and pointed, or obtuse, others with only lightly traced lobes; triangular or closed serrations; usually with a red tinge when adult; heartshaped footstalk.

Tinta Negra is easily identified by its leaves, which in autumn are an intense scarlet colour, with red patches.

Tendrils: few.

Bunches: medium to large bunches; globular or elliptical – globular grapes, equal or unequal, of 12/18mm, soft or not very hard, red with a clear colour

Grapes: medium and uniformly round, generally between 12/25mm; not very hard, a red colour when ripe; and not very waxy. A clear pulp, medium consistency, very succulent. The musts are not particularly concentrated, with a potential alcohol of between 9 and 12ºC.

MADEIRA STYLES

As far as Madeira wine is concerned, it is certainly true to say that "the older the better". The best Madeira wines are the oldest, in particular those known as "Frasqueiras" or "Garrafeiras". However, there are also others Madeira wines of excellent quality available on the market.

The majority of Madeira wines are made up from blend of different grape varieties. The red grape Tinta Negra, is usually the predominant variety in these blends. This style of Madeira is then presented to the market according to the time it has spent aging in oak casks or vats, labelled as "Madeira Wine".

Single varietal wines are also made, including Sercial, Verdelho, Bual (or Boal), Malvasia and Terrantez. These wines are branded and presented to the market according to their grape variety, as Colheitas (see below) or by the number of years spent aging in cask.

Traditional mentions for wines with indication of the year of harvest.

Frasqueira or Garrafeira

Reserved reference to the wine with indication of the vintage year and recommended vine variety, produced by the canteiro system and submitted to minimum continuous ageing of 20 years in wooden casks showing organoleptic characteristics of exceptional quality, where the bottling year should be indicated and it should have a specific current account before and after bottling.

Colheita

Reserved reference to the wine with indication of the vintage year, that has been aged continuously in wooden casks during at least 5 years and shows special organoleptic characteristics, where the start of the ageing process should be indicated to the IVBAM, PI - RAM at least 5 business days in advance, as well as its end, with indication of the bottling year and it should have a specific current account.

Solera

Reserved reference to the wine produced by the canteiro system, which shows special organoleptic characteristics and whose base wine is of only one harvest and just one recommended vine variety and submitted to a minimum continuous ageing of 5 years in wooden casks, which constitutes the base of a batch. After this period, a quantity that does not exceed 10% can be removed annually from each of the casks, which is replaced by the same quantity of another younger wine of the same variety, up to the maximum of 10 additions. Only after the existing wine has been submitted to this process can it be bottled as Solera. Each of the additions and each bottling should be communicated to IVBAM, PI - RAM, at least 5 business days in advance. This reference should be accompanied by indication of the harvest year of the base wine, the vine variety and the bottling year and it should have a specific current account before and after bottling.

Traditional mentions for wines with indication of age

Reserva, Velho, Reserve, Old or Vieux, wine in conformity with the standard of 5 years old;

Reserva Velha, Reserva Especial, Muito Velho, Old Reserve, Special Reserve ou Very Old, Madeira wine in conformity with the standard of 10 years old;

Reserva Extra or Extra Reserve, Madeira wine in conformity with the standard of 15 years old.

They may also be used in labeling according to the production process, color, structure and other characteristics, one or more of the following designations.

Canteiro – Madeira wine fortified during or right after fermentation, being submitted to ageing in wooden casks for a minimum period of 2 years, it should have a specific current account and cannot be subjected to the heating production process (estufagem) nor bottled with less than 3 years, counted as of 1 January of the year following that of the harvest.

Rainwater – Wine with a pale to golden colour, with a Baumé degree between 1.0 and 2.5, which may also be associated to the indication of maximum age of 10 years or other equivalent.

Seleccionado, Selected Choice or Finest - Madeira wine showing special quality for the age in question.

Fino or Fine – Madeira wine of quality with perfect balance.

Wine with Indication of Age

Madeira Wine with the right to the use of the designation of age, when its quality is in conformity with the respective standards, with the permitted age indications being the following: 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and over 50 years old.

As far as the degree of sweetness the different styles of Madeira wine are classified as follows:

Dry - with less than 1.5º Baumé.

The classification “Extra Seco” can is used when Baumé is less than 0.5º.

Medium Dry – between 1.0º and 2.5 Bé.

Medium Sweet – between 2.5º and 3.5 Bé.

Sweet (Doce) – over 3.5º Bé.

The majority of Madeira wines are made up from blend of different grape varieties. The red grape Tinta Negra, is usually the predominant variety in these blends. This style of Madeira is then presented to the market according to the time it has spent aging in oak casks or vats, labelled as "Madeira Wine".

Single varietal wines are also made, including Sercial, Verdelho, Bual (or Boal), Malvasia and Terrantez. These wines are branded and presented to the market according to their grape variety, as Colheitas (see below) or by the number of years spent aging in cask.

Traditional mentions for wines with indication of the year of harvest.

Frasqueira or Garrafeira

Reserved reference to the wine with indication of the vintage year and recommended vine variety, produced by the canteiro system and submitted to minimum continuous ageing of 20 years in wooden casks showing organoleptic characteristics of exceptional quality, where the bottling year should be indicated and it should have a specific current account before and after bottling.

Colheita

Reserved reference to the wine with indication of the vintage year, that has been aged continuously in wooden casks during at least 5 years and shows special organoleptic characteristics, where the start of the ageing process should be indicated to the IVBAM, PI - RAM at least 5 business days in advance, as well as its end, with indication of the bottling year and it should have a specific current account.

Solera

Reserved reference to the wine produced by the canteiro system, which shows special organoleptic characteristics and whose base wine is of only one harvest and just one recommended vine variety and submitted to a minimum continuous ageing of 5 years in wooden casks, which constitutes the base of a batch. After this period, a quantity that does not exceed 10% can be removed annually from each of the casks, which is replaced by the same quantity of another younger wine of the same variety, up to the maximum of 10 additions. Only after the existing wine has been submitted to this process can it be bottled as Solera. Each of the additions and each bottling should be communicated to IVBAM, PI - RAM, at least 5 business days in advance. This reference should be accompanied by indication of the harvest year of the base wine, the vine variety and the bottling year and it should have a specific current account before and after bottling.

Traditional mentions for wines with indication of age

Reserva, Velho, Reserve, Old or Vieux, wine in conformity with the standard of 5 years old;

Reserva Velha, Reserva Especial, Muito Velho, Old Reserve, Special Reserve ou Very Old, Madeira wine in conformity with the standard of 10 years old;

Reserva Extra or Extra Reserve, Madeira wine in conformity with the standard of 15 years old.

They may also be used in labeling according to the production process, color, structure and other characteristics, one or more of the following designations.

Canteiro – Madeira wine fortified during or right after fermentation, being submitted to ageing in wooden casks for a minimum period of 2 years, it should have a specific current account and cannot be subjected to the heating production process (estufagem) nor bottled with less than 3 years, counted as of 1 January of the year following that of the harvest.

Rainwater – Wine with a pale to golden colour, with a Baumé degree between 1.0 and 2.5, which may also be associated to the indication of maximum age of 10 years or other equivalent.

Seleccionado, Selected Choice or Finest - Madeira wine showing special quality for the age in question.

Fino or Fine – Madeira wine of quality with perfect balance.

Wine with Indication of Age

Madeira Wine with the right to the use of the designation of age, when its quality is in conformity with the respective standards, with the permitted age indications being the following: 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and over 50 years old.

As far as the degree of sweetness the different styles of Madeira wine are classified as follows:

Dry - with less than 1.5º Baumé.

The classification “Extra Seco” can is used when Baumé is less than 0.5º.

Medium Dry – between 1.0º and 2.5 Bé.

Medium Sweet – between 2.5º and 3.5 Bé.

Sweet (Doce) – over 3.5º Bé.

HARVEST

Harvest usually starts in the last week of August and continues throughout September. The vinification department in the Madeira Wine Institute (Instituto do Vinho, Bordado e Artesanato da Madeira) declares the official start and end date for harvest.

Grapes may be harvested earlier than official date if authorised by the IVBAM. This is exceptional and tends to happen when the maturation of the grapes is likely to be accelerated by hot, sunny, dry weather.

Location and the weather conditions during the development of the grape are the most influential factors in the decision to bring forward the date of harvest. It is most commonly done where there are older vines and/or to vines planted in the southern, sunnier areas of the island, notably in the region of Câmara de Lobos.

In a typical year, harvest will begin two weeks later on the north facing slopes, which are cooler and have more rainfall.

For the production of fortified wine, the vineyards are allowed legal maximum of 80 hl of must per hectare with a minimum of naturally occurring alcohol of 9%. The IVBAM can chose to alter this limit, taking into consideration the specific conditions of the period.

Vines are grown on the hillsides of the island, in small terraces or walled areas known as “poios”. These stretch all the way to the sea, surrounded by supportive grey basalt stone walls, which make mechanisation almost impossible.

Picking the grapes by hand is the only viable harvesting method in Madeira, due both to the geophysical conditions of the island and because most grapes continue to be grown traditionally, trained along low pergolas over the soil. The work of maintaining, treating and harvesting the grapes is greatly complicated by this trellis system.

As a result of these factors, the effort of working a vineyard and the cost of cultivating the grapes is extremely high.

There are changes to the island’s vineyard landscape happening at this point in time. Some new vineyards are being planted in the more efficient espalier layout.

The Portuguese system of dividing the land between each member of successive generations is the reason that Justino’s Madeira Wines like most other Madeira wine producers, do not have their own vineyard. There are numerous growers spread throughout the island that supply grapes to our winery during harvest.

The price paid for the grapes to the growers varies according to the condition of the fruit and the level of alcohol in the grape. The company will decide the prices and inform the growers of these at the beginning of each season.

Grapes may be harvested earlier than official date if authorised by the IVBAM. This is exceptional and tends to happen when the maturation of the grapes is likely to be accelerated by hot, sunny, dry weather.

Location and the weather conditions during the development of the grape are the most influential factors in the decision to bring forward the date of harvest. It is most commonly done where there are older vines and/or to vines planted in the southern, sunnier areas of the island, notably in the region of Câmara de Lobos.

In a typical year, harvest will begin two weeks later on the north facing slopes, which are cooler and have more rainfall.

For the production of fortified wine, the vineyards are allowed legal maximum of 80 hl of must per hectare with a minimum of naturally occurring alcohol of 9%. The IVBAM can chose to alter this limit, taking into consideration the specific conditions of the period.

Vines are grown on the hillsides of the island, in small terraces or walled areas known as “poios”. These stretch all the way to the sea, surrounded by supportive grey basalt stone walls, which make mechanisation almost impossible.

Picking the grapes by hand is the only viable harvesting method in Madeira, due both to the geophysical conditions of the island and because most grapes continue to be grown traditionally, trained along low pergolas over the soil. The work of maintaining, treating and harvesting the grapes is greatly complicated by this trellis system.

As a result of these factors, the effort of working a vineyard and the cost of cultivating the grapes is extremely high.

There are changes to the island’s vineyard landscape happening at this point in time. Some new vineyards are being planted in the more efficient espalier layout.

The Portuguese system of dividing the land between each member of successive generations is the reason that Justino’s Madeira Wines like most other Madeira wine producers, do not have their own vineyard. There are numerous growers spread throughout the island that supply grapes to our winery during harvest.

The price paid for the grapes to the growers varies according to the condition of the fruit and the level of alcohol in the grape. The company will decide the prices and inform the growers of these at the beginning of each season.

VINIFICATION

THE RECEPTION AND SELECTION OF GRAPES

The production of Madeira wine begins when the grapes are selected during harvest. The quality of the wine depends first and foremost on this selection. We try to keep to a minimum the length of time between the picking and the pressing of the grapes, given the fact that this is vital to maintaining quality. By using small boxes to carry up to 30 - 50kg, the grapes can be quickly transported, avoiding the risk being crushed under their own weight, or allowing fermentation and oxidation to begin, with a corresponding loss of flavour.

The grapes are sorted on arrival, primarily to check their condition. Then they are weighed, and the probable level of alcohol is measured. The grapes are then selected for vinification, according to the different styles of wine to be made.

An incentive scheme is in place by which payment varies according to the level of alcohol found, thereby encouraging the growers to allow their grapes to ripen as fully as possible.

The white grape varieties, Sercial, Verdelho, Boal, and Malvasia, go through the vinification process entirely separately to other varieties. However, the various red grape varieties, primarily Tinta Negra, and Complexa are vinified together. The nature of the must produced by the various varieties is directly a result of the soil type and climatic conditions of the area in which they were cultivated.

DESTALKING, CRUSHING, EXTRACTION, PRESSING, AND FERMENTATION

The grapes are completely destalked before any crushing, extraction, pressing or fermentation takes place. This ensures that the stringent and bitter flavours of the stalks do not taint the wines.

After destalking, vinification follows one of two distinct formats:

Crushing, extraction, pressing and fermentation

Crushing, fermentation, extraction and pressing

In either case, fermentation (with or without skin maceration) is regulated by temperature controlled stainless steel vats.

In the case of fermentation on the skins, the pumping over is automatically controlled.

FORTIFICATION

Fermentation is stopped by the addition of grape spirit in order to obtain wines with different levels of sweetness.

The grape spirit is added at an exact point in time, chosen to reflect the style of wine being created. The grape neutral spirit is 96% proof, and its addition stops fermentation almost instantaneously.

Malmsey, Bual and other sweet or medium sweet Madeira wines are fortified first, in order to guarantee a higher level of residual sugar. Fermentation of Sercial, Verdelho and other dry or medium dry Madeira wines runs until almost all the natural sugar found in the grape has been converted into alcohol. After fortification, the wines achieve between 17 % and 18% of alcohol by volume.

ESTUFAGEM

After fortification, clarification and separation into different batches has taken place, but prior to being aged in oak casks, the majority of wines undergo the process of “estufagem”. Estufagem” is a traditional method of heating the wine, unique to Madeira. The wine is placed into stainless steel vats which are heated by coils of hot water (the “estufas”). The vats are heated for up to 3 months to temperatures of between 45 and 50 degrees C.

The Madeira Wine Institute (IVBAM) controls this process, during which time the vats remain sealed. In order to monitor the quality of the wine, samples are taken to be analysed both before and after estufagem.

Madeira wine which has not undergone estufagem is known as “canteiro”, “vinho – canteiro”, or “vinho de canteiro.” Once these wines have been clarified, corrected and divided into different lots, these wines are aged in oak casks. This system is used for all wines that have been made from white grape varieties, namely Malvasia, Boal, Verdelho, Sercial, and sometimes those of Tinta Negra.

AGING

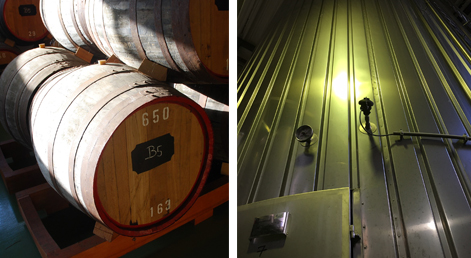

The best wines begin the aging process in oak casks or vats, of varying sizes, whether or not they have been through the estufagem process.

The aging process uses casks or “tonels” made from French, American or Portuguese oak, of 300, 350, 450, 650, 1.200 to 2.450 litres in size. The wooden vats, also made of French oak, hold anything between 9.600 to 42.000 litres.

A wine’s quality, character and potential determines its selection for aging. The wine develops a uniquely complex and intense flavour thanks to the oxidation it undergoes as a result of aging in cask in a subtropical climate.

The length of time a wine is left to age is a technical decision, depending on the style of wine to be created, and market demand.

The oenologist and technicians at Justino’s Madeira continually taste the wine throughout the aging process to monitor its evolution and quality. During this time, the wine is racked, divided into barrels and undergoes any necessary corrections, in order to ensure that it continues to develop in a balanced and harmonious fashion.

Justino’s, Madeira Wines, S.A., is dedicated to safeguarding and improving the acknowledged quality of its wines.

By monitoring and controlling the ripening of the grapes and developing ever closer relationships with the growers, and by using modern technology and rigorously controlling the vinification, estufagem, and aging of the wine, we continuously improve the quality of our wines, particularly the younger ones. This allows us to offer wide variety of Madeira wines to our consumers.

The production of Madeira wine begins when the grapes are selected during harvest. The quality of the wine depends first and foremost on this selection. We try to keep to a minimum the length of time between the picking and the pressing of the grapes, given the fact that this is vital to maintaining quality. By using small boxes to carry up to 30 - 50kg, the grapes can be quickly transported, avoiding the risk being crushed under their own weight, or allowing fermentation and oxidation to begin, with a corresponding loss of flavour.

The grapes are sorted on arrival, primarily to check their condition. Then they are weighed, and the probable level of alcohol is measured. The grapes are then selected for vinification, according to the different styles of wine to be made.

An incentive scheme is in place by which payment varies according to the level of alcohol found, thereby encouraging the growers to allow their grapes to ripen as fully as possible.

The white grape varieties, Sercial, Verdelho, Boal, and Malvasia, go through the vinification process entirely separately to other varieties. However, the various red grape varieties, primarily Tinta Negra, and Complexa are vinified together. The nature of the must produced by the various varieties is directly a result of the soil type and climatic conditions of the area in which they were cultivated.

DESTALKING, CRUSHING, EXTRACTION, PRESSING, AND FERMENTATION

The grapes are completely destalked before any crushing, extraction, pressing or fermentation takes place. This ensures that the stringent and bitter flavours of the stalks do not taint the wines.

After destalking, vinification follows one of two distinct formats:

Crushing, extraction, pressing and fermentation

Crushing, fermentation, extraction and pressing

In either case, fermentation (with or without skin maceration) is regulated by temperature controlled stainless steel vats.

In the case of fermentation on the skins, the pumping over is automatically controlled.

FORTIFICATION

Fermentation is stopped by the addition of grape spirit in order to obtain wines with different levels of sweetness.

The grape spirit is added at an exact point in time, chosen to reflect the style of wine being created. The grape neutral spirit is 96% proof, and its addition stops fermentation almost instantaneously.

Malmsey, Bual and other sweet or medium sweet Madeira wines are fortified first, in order to guarantee a higher level of residual sugar. Fermentation of Sercial, Verdelho and other dry or medium dry Madeira wines runs until almost all the natural sugar found in the grape has been converted into alcohol. After fortification, the wines achieve between 17 % and 18% of alcohol by volume.

ESTUFAGEM

After fortification, clarification and separation into different batches has taken place, but prior to being aged in oak casks, the majority of wines undergo the process of “estufagem”. Estufagem” is a traditional method of heating the wine, unique to Madeira. The wine is placed into stainless steel vats which are heated by coils of hot water (the “estufas”). The vats are heated for up to 3 months to temperatures of between 45 and 50 degrees C.

The Madeira Wine Institute (IVBAM) controls this process, during which time the vats remain sealed. In order to monitor the quality of the wine, samples are taken to be analysed both before and after estufagem.

Madeira wine which has not undergone estufagem is known as “canteiro”, “vinho – canteiro”, or “vinho de canteiro.” Once these wines have been clarified, corrected and divided into different lots, these wines are aged in oak casks. This system is used for all wines that have been made from white grape varieties, namely Malvasia, Boal, Verdelho, Sercial, and sometimes those of Tinta Negra.

AGING

The best wines begin the aging process in oak casks or vats, of varying sizes, whether or not they have been through the estufagem process.

The aging process uses casks or “tonels” made from French, American or Portuguese oak, of 300, 350, 450, 650, 1.200 to 2.450 litres in size. The wooden vats, also made of French oak, hold anything between 9.600 to 42.000 litres.

A wine’s quality, character and potential determines its selection for aging. The wine develops a uniquely complex and intense flavour thanks to the oxidation it undergoes as a result of aging in cask in a subtropical climate.

The length of time a wine is left to age is a technical decision, depending on the style of wine to be created, and market demand.

The oenologist and technicians at Justino’s Madeira continually taste the wine throughout the aging process to monitor its evolution and quality. During this time, the wine is racked, divided into barrels and undergoes any necessary corrections, in order to ensure that it continues to develop in a balanced and harmonious fashion.

Justino’s, Madeira Wines, S.A., is dedicated to safeguarding and improving the acknowledged quality of its wines.

By monitoring and controlling the ripening of the grapes and developing ever closer relationships with the growers, and by using modern technology and rigorously controlling the vinification, estufagem, and aging of the wine, we continuously improve the quality of our wines, particularly the younger ones. This allows us to offer wide variety of Madeira wines to our consumers.

ILLNESS AND PLAGUES

INTRODUCTION

From the mid XVIII century onwards, the production of Madeira wine kept increasing until the 1820’s.

The vineyards on the island were able to evolve to meet market demand, and the British influence in Madeira helped secure a privileged destiny for Madeira.

In fact, the overwhelming popularity of Madeira wine was largely due to the nature of European and colonial political and economic reality. During periods of conflict, the colonies were closed off from Europe, and this opened up a ready market for the island’s wines. The colonial market weighed so heavily on the island’s capacity to supply wine, that there were times when demand exceeded supply. In the face of unbridled demand, and given the low volume of quality wine available, the shippers resorted to exporting inferior wines, previously destined for internal consumption, or for distillation to produce brandy.

In order to meet demand, attention turned to increasing the volume of grapes grown on the island, and less care was taken in the production and aging of wines. When market demand from Europe normalised, the Madeiran economy slid into recession.

Madeira wine began to fall in popularity, due not to the competition from other wines, such as Port and Sherry, but also because of the poor reputation the wine had in its traditional markets. This was as a result of the low quality of exported wine, and also because of a number of cases of fraud. All this meant that the price paid for Madeiran wine fell considerably.

The impending crisis in Madeira’s viniculture was anticipated by the arrival of oidium (Oidium tuckerii or “powdery mildew”) on the island in the mid nineteenth century. Oidium was more commonly known to the Madeiran’s as "mangra". Some years later, the appearance of phylloxera provoked further change in the island’s viticulture.

Despite natural disasters and the oidium and phylloxera plagues, Madeira wine survived, and is today one of the mainstays of the island’s economy, together with tourism and the banana crop.

THE SPREAD OF OIDIUM

Oidium came from the United States and was first detected in Europe in 1847 when it was found in France. It is alleged that it reached Madeira in 1851, and said to have been brought in with some imported plants. Included amongst these were some French varieties, which are thought to have been infected by the fungus.

The disease spread rapidly throughout the island encouraged by the subtropical, warm and humid climate. It attacked the areas of Funchal and Machico with particular force, and devastated the majority of the island’s vineyards, resulting in a predictable decimation of production and quality of wine. The effect it had on the island’s economy was quickly felt; given that viniculture was the main source of earnings. In only three years (1852 – 1854) the production averages fell from 50,000 hl to only 600 hl.

Brushing the vines with sulphur proved to be the best method of treating and preventing the disease. Some of the vines were saved; but this did not stop the farmers from turning their attention once again to the cultivation of sugar cane rather than replanting their vineyards.

PHYLLOXERA

One of the reasons that phylloxera successfully invaded Europe is because of the oidium plague, which resulted in growers turning to vine stock resistant to oidium.

This vine louse probably had a greater effect on the production of wine than any other plague or disease. Until phylloxera arrived, most vines were planted on their own roots, that is to say they were not grafted.

The desperate search for a remedy to the oidium crisis, led the growers to plant the Vitis Labrusca (Isabella) variety, which was oidium resistant, and first arrived on the island in 1865. However these proved to be carriers of an even more ferocious disease that would create a far greater devastation than the last, until a means of controlling phylloxera could be found.

growers to plant the Vitis Labrusca (Isabella) variety, which was oidium resistant, and first arrived on the island in 1865. However these proved to be carriers of an even more ferocious disease that would create a far greater devastation than the last, until a means of controlling phylloxera could be found.

The first symptoms of the disease were identified in São Gonçalo and São Roque in 1872, but it quickly spread throughout the island and was still active as late as 1908. It is estimated that in 1883, 80% or more of the island’s vineyards were infested by phylloxera.

In varieties susceptible to the disease, which includes those of the Vitis vinifera species, (commonly known as viniferous or European stock) the louse feeds off the sap in the plant. The action of biting into the roots causes nodules and warts to grow, which develop into fissures, causing the root to rot. As the roots rot, the leaves on the vines begin to lose their colour, a sign that the vine is withering and soon to die.

In 1883, only 500 ha of the 2500 ha of vineyards planted before phylloxera struck were still extant.

The European varieties, that had once existed on the island and that had been the basis of the fame of Madeira wine, were almost completely wiped out. Malvasia survived only in Fajã dos Padres.

Just as in France, every effort was made to control and halt the progress of the plague. The practice of flooding the vineyards for some weeks during the winter, successfully tested in France, was not viable given the layout of the terrain.

Despite having had some limited success, the use of sulphide injections had no effect in most places.

It was the practice of grafting a European variety onto phylloxera resistant American root stock that proved to be the most successful way to combat the disease. As a result, the island’s vines were no longer planted on their own stock, but slowly replanted with the grafted varieties.

The resistance developed by American vines to phylloxera comes as result of the formation of layers of bark covering the wounds inflicted by the louse as it feeds. The formation of this protective layer successfully prevents the invasion of other fungi or bacterium, which would eventually lead the roots to rot, and the vine to die. As phylloxera is native to North America, it is no surprise that various endemic American root stocks have evolved a method of defence against this disease.

When these resistant varieties are attacked by the louse, their only reaction is the development of a small growth on their leaves, as the roots no longer suffer any real damage.

In 1882, the Anti-phylloxera commission on the island became responsible for the distribution and re-plantation of vineyards, using shoots of American varieties handed out for free to the growers. Two nurseries were established, and by 1883 some 60,000 vines had been distributed. However, it was not an easy task to replant the island’s vineyards. It took some time for the vine to regain its economic strength on the island; the growers were unmotivated, many of the English merchants had left the island, and the turmoil felt in one of the wine’s major markets, the English colonies, all contributed to the difficulties felt at the time.

Experience showed that not all the American varieties were able to adapt to the growing conditions on the island, or were incompatible with the traditional varieties. The preferred stocks were Vitis riparia, Herbemont, Cunningham and Jacquet (Black Spanish), all of which were well suited to conditions on the island.

From the mid XVIII century onwards, the production of Madeira wine kept increasing until the 1820’s.

The vineyards on the island were able to evolve to meet market demand, and the British influence in Madeira helped secure a privileged destiny for Madeira.

In fact, the overwhelming popularity of Madeira wine was largely due to the nature of European and colonial political and economic reality. During periods of conflict, the colonies were closed off from Europe, and this opened up a ready market for the island’s wines. The colonial market weighed so heavily on the island’s capacity to supply wine, that there were times when demand exceeded supply. In the face of unbridled demand, and given the low volume of quality wine available, the shippers resorted to exporting inferior wines, previously destined for internal consumption, or for distillation to produce brandy.

In order to meet demand, attention turned to increasing the volume of grapes grown on the island, and less care was taken in the production and aging of wines. When market demand from Europe normalised, the Madeiran economy slid into recession.

Madeira wine began to fall in popularity, due not to the competition from other wines, such as Port and Sherry, but also because of the poor reputation the wine had in its traditional markets. This was as a result of the low quality of exported wine, and also because of a number of cases of fraud. All this meant that the price paid for Madeiran wine fell considerably.

The impending crisis in Madeira’s viniculture was anticipated by the arrival of oidium (Oidium tuckerii or “powdery mildew”) on the island in the mid nineteenth century. Oidium was more commonly known to the Madeiran’s as "mangra". Some years later, the appearance of phylloxera provoked further change in the island’s viticulture.

Despite natural disasters and the oidium and phylloxera plagues, Madeira wine survived, and is today one of the mainstays of the island’s economy, together with tourism and the banana crop.

THE SPREAD OF OIDIUM

Oidium came from the United States and was first detected in Europe in 1847 when it was found in France. It is alleged that it reached Madeira in 1851, and said to have been brought in with some imported plants. Included amongst these were some French varieties, which are thought to have been infected by the fungus.

The disease spread rapidly throughout the island encouraged by the subtropical, warm and humid climate. It attacked the areas of Funchal and Machico with particular force, and devastated the majority of the island’s vineyards, resulting in a predictable decimation of production and quality of wine. The effect it had on the island’s economy was quickly felt; given that viniculture was the main source of earnings. In only three years (1852 – 1854) the production averages fell from 50,000 hl to only 600 hl.

Brushing the vines with sulphur proved to be the best method of treating and preventing the disease. Some of the vines were saved; but this did not stop the farmers from turning their attention once again to the cultivation of sugar cane rather than replanting their vineyards.

PHYLLOXERA

One of the reasons that phylloxera successfully invaded Europe is because of the oidium plague, which resulted in growers turning to vine stock resistant to oidium.

This vine louse probably had a greater effect on the production of wine than any other plague or disease. Until phylloxera arrived, most vines were planted on their own roots, that is to say they were not grafted.

The desperate search for a remedy to the oidium crisis, led the

growers to plant the Vitis Labrusca (Isabella) variety, which was oidium resistant, and first arrived on the island in 1865. However these proved to be carriers of an even more ferocious disease that would create a far greater devastation than the last, until a means of controlling phylloxera could be found.

growers to plant the Vitis Labrusca (Isabella) variety, which was oidium resistant, and first arrived on the island in 1865. However these proved to be carriers of an even more ferocious disease that would create a far greater devastation than the last, until a means of controlling phylloxera could be found.The first symptoms of the disease were identified in São Gonçalo and São Roque in 1872, but it quickly spread throughout the island and was still active as late as 1908. It is estimated that in 1883, 80% or more of the island’s vineyards were infested by phylloxera.

In varieties susceptible to the disease, which includes those of the Vitis vinifera species, (commonly known as viniferous or European stock) the louse feeds off the sap in the plant. The action of biting into the roots causes nodules and warts to grow, which develop into fissures, causing the root to rot. As the roots rot, the leaves on the vines begin to lose their colour, a sign that the vine is withering and soon to die.

In 1883, only 500 ha of the 2500 ha of vineyards planted before phylloxera struck were still extant.

The European varieties, that had once existed on the island and that had been the basis of the fame of Madeira wine, were almost completely wiped out. Malvasia survived only in Fajã dos Padres.

Just as in France, every effort was made to control and halt the progress of the plague. The practice of flooding the vineyards for some weeks during the winter, successfully tested in France, was not viable given the layout of the terrain.

Despite having had some limited success, the use of sulphide injections had no effect in most places.

It was the practice of grafting a European variety onto phylloxera resistant American root stock that proved to be the most successful way to combat the disease. As a result, the island’s vines were no longer planted on their own stock, but slowly replanted with the grafted varieties.

The resistance developed by American vines to phylloxera comes as result of the formation of layers of bark covering the wounds inflicted by the louse as it feeds. The formation of this protective layer successfully prevents the invasion of other fungi or bacterium, which would eventually lead the roots to rot, and the vine to die. As phylloxera is native to North America, it is no surprise that various endemic American root stocks have evolved a method of defence against this disease.

When these resistant varieties are attacked by the louse, their only reaction is the development of a small growth on their leaves, as the roots no longer suffer any real damage.

In 1882, the Anti-phylloxera commission on the island became responsible for the distribution and re-plantation of vineyards, using shoots of American varieties handed out for free to the growers. Two nurseries were established, and by 1883 some 60,000 vines had been distributed. However, it was not an easy task to replant the island’s vineyards. It took some time for the vine to regain its economic strength on the island; the growers were unmotivated, many of the English merchants had left the island, and the turmoil felt in one of the wine’s major markets, the English colonies, all contributed to the difficulties felt at the time.

Experience showed that not all the American varieties were able to adapt to the growing conditions on the island, or were incompatible with the traditional varieties. The preferred stocks were Vitis riparia, Herbemont, Cunningham and Jacquet (Black Spanish), all of which were well suited to conditions on the island.

THE ISLAND OF WINE

It is almost certain that the first settlers brought with them the first vines from Portugal. Later on, Mediterranean vine stock was introduced.

Following the instructions of the King of Portugal and Prince Henry the Navigator, the governors of the Madeiran archipelago, João Gonçalves Zarco, Tristão Vaz Teixeira and Bartolomeu Perestrelo, cleared the earth and planted various crops brought in from Portugal. These included sugar cane from Sicily, and vines from Candia in Greece, specifically the vine stock known as Malvasia.

Following the instructions of the King of Portugal and Prince Henry the Navigator, the governors of the Madeiran archipelago, João Gonçalves Zarco, Tristão Vaz Teixeira and Bartolomeu Perestrelo, cleared the earth and planted various crops brought in from Portugal. These included sugar cane from Sicily, and vines from Candia in Greece, specifically the vine stock known as Malvasia.

According to contemporary sources, the Venetian explorer, Cadamosto, visited the island in 1455 and was amazed by the vineyards that had been established in such a short time in Funchal, as well as by the quality and quantity of wine produced.

The decline of the sugar industry came early on in the history of Madeira, although not before it had significantly contributed to the island’s wealth, and to its socio-economical and cultural development. The industry declined partly as a result of competition from other sugar producing areas, mainly Brazil and Central America, and also because of the restricted size of agricultural land on the island.

As a result, vines became the most important crop in Madeira, the focus of knowledge and effort for the farmers, and the driving force in the island’s economy.

Due to this reliance on a monoculture crop, Madeira quickly become dependant on external markets and imported goods. As wine made in Madeira became a marketable commodity, and trading with other nations became established, the English quickly became influential. Many of the early merchants were English, who began to dominate the marketplace in the exchange of Madeira wine for wheat and American corn, European textiles and manufactured goods.

The island’s location in the Atlantic close to the various trade routes between Europe and the Indies, North America, Brazil and Africa brought innumerable advantages. As well as becoming a vital trading post, Madeira was left on the margins of the various conflicts that besieged Europe, such as the war of Austrian succession (1740 – 1748), the Seven Year War, the French Revolution (1789) and the ensuing blockade of continental trade (1806). Only the war of American Independence (1776 – 1790) profoundly affected Madeira, as a result of the instability of one of the major markets for Madeira Wine.

THE ENGLISH AND MADEIRA

The evolution of the wine trade has always been closely linked to the political and economic reality in Europe and her colonies. Madeira was brought under England’s sphere of influence and given a key role as a result of various treaties, dating from the seventeenth century onward.

At the time, England’s trade laws (Navigation Act 1660) stipulated that all exports to English colonies could only be undertaken by ships of English provenance, sailing from and returning to London.

However, as result of the marriage between Catherine of Braganza and Charles II of England, the Staple Act (1663) was passed. Thanks to this, Madeira and the Azores were exempt from the prohibition of the Navigation Act, and became key suppliers for wine.

The various treaties between England and Portugal strengthened the position of the English merchants on the island, and the growth of the wine trade is intimately linked to the English presence in Madeira.

English merchants were quick to recognise the quality of wine produced in Madeira, and traded it widely throughout Europe and the colonies. In this way, Madeira became known as "the island of wine" to the English.

When North America was colonised by England in the seventeenth century, Madeira gained one of its biggest markets.

Over the years, Madeira Wine has become available in many other markets. However, the English were its first and most fervent appreciators, with records of imports dating back to the fifteenth century.

At the time, England’s trade laws (Navigation Act 1660) stipulated that all exports to English colonies could only be undertaken by ships of English provenance, sailing from and returning to London.

However, as result of the marriage between Catherine of Braganza and Charles II of England, the Staple Act (1663) was passed. Thanks to this, Madeira and the Azores were exempt from the prohibition of the Navigation Act, and became key suppliers for wine.